Biography

1955

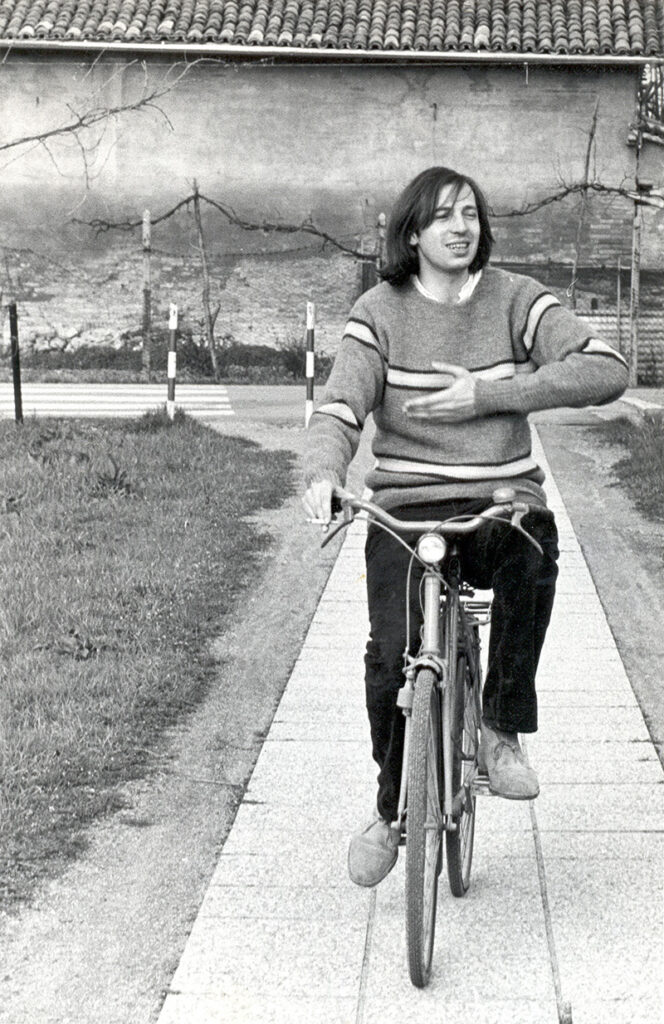

Pier Vittorio Tondelli was born in Correggio, in the province of Reggio Emilia, on 14 September 1955.

He lived his childhood with his parents Brenno and Marta and his brother Giulio, in an environment that he himself describes as one of ‘ordinary people, people who beat the provincial and municipal roads, people far removed from the news and gossip’. The memories of the child Tondelli go back to the pigeons of his grandfather Dembrao and father Brenno (‘My grandfather Dembrao always wanted me to keep up with his homing pigeons and that is why, after school, I would take my bicycle and go to visit him, just outside the city, in the house where he lived…’), to his grandmother who took him to the city’s main square. ‘), to his grandmother carrying him in her arms in front of the little chapel with the altar of the Virgin Mary and the vases of flowers, but also to the games with bows and arrows, ‘the ones we used to make with our flock of barely adolescent friends in the fields and meadows, with treacherous arrows and warlike intentions: We used to hunt frogs along ditches and canals, to make trophies and decorations to be placed in the straw huts, in whose shade we would park our bicycles’.

1967

At the age of 12, he began to frequent the municipal library, with which he maintained a regular relationship over the years. This is how he remembers the library he first entered as a boy:

‘The old library was located in the wing of a 16th-century palace now set up as the Museo Civico. A coffered ceiling decorated and painted, and huge walls of old books on which probably still hovered the spirit of the person who lived in those rooms, the poetess Veronica Gambara, the Nicolò Postumo author of Fabula de Cefalo, the caretaker perpetually with a Tuscan slurp in his mouth and terrible towards us children, always seen as spoilers or pain in the ass.

He mainly reads adventure novels and the first two he borrows are Salgari’s The Tigers of Monpracem and Baroness Orczy’s The Red Pimpernel.

Among his ‘childhood’ readings, he mentions ‘a Journey to the Centre of the Earth in a “luxury” plasticized binding, published in April 1963 by the Boschi publishing house in Milan, a Boris Gudunòv by Edizioni Paoline, a 1954 I ragazzi della via Paal by the Malipiero publishing house in Bologna. In the ‘Mughetto’ series from the publisher Carroccio a Treasure Island. For the series ‘Sui sentieri del West’, edited by Tullio Kezich and Roberto Leydi here is I tre cavalieri di Alamo. For the Principato editions another Giulio Verne, North against South. The format of these books is more or less that of a news magazine. The typefaces are in a very readable body, the covers are colourful and from time to time there are illustrations, simple black and white sketches or plates outside the text’.

1969-1974

He attended the Liceo Classico ‘Rinaldo Corso’ in Correggio and took part in the life of the youth communities of Catholic associations. He wrote his first texts for cyclostyled magazines, published in the oratorian sphere. He often remembers summers in the mountains, with the soundtrack of Lucio Battisti and Fiori rosa, fiori di pesco ‘sung at the top of his voice on the summer camp bus’ or the choirs around bonfires ‘with ten guitars at a time conducting young, melancholic, love-struck uvulas, before the revolution’.

Everyone calls him Vicky and that is how he signed his first writings and also the theatrical reduction for a play, performed in Correggio, from Antoine De Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince. This is how he explains the reasons for his choice: ‘This book is not a kind of fable estranged from the other writings and philosophy of the “poet-aviator”, it is perhaps instead its synthesis. The longing for childhood, for fantasy, that lyrical humanitarianism that predominates in Terra degli uomini and from which the Pilot’s monologues have been excerpted, the irony towards any greatness and eagerness for power, the poetic discourse on responsibility and love that takes shape in the poignant episode of the taming of the fox, the exhortation to a spiritual life, to meditation (‘the essential is invisible to the eyes’ repeats the Little Prince as he follows his fox), all these motifs are present and envelop the fable with greater clarity than any other literary form. These are therefore the most rational motivations for our choice that emerge directly from the text and that we have tried to communicate in the performance’.

1975-1978

The soundtrack changed and so did the generational references: ‘Battisti was then abandoned around 1977, not because they did not like his songs, but perhaps because they had grown up and it was already the time of Francesco Guccini, Francesco De Gregori, Antonello Venditti, Inti Illimani and, for better or worse, they had gone through the unparalleled radio experience of Per voi giovani’.

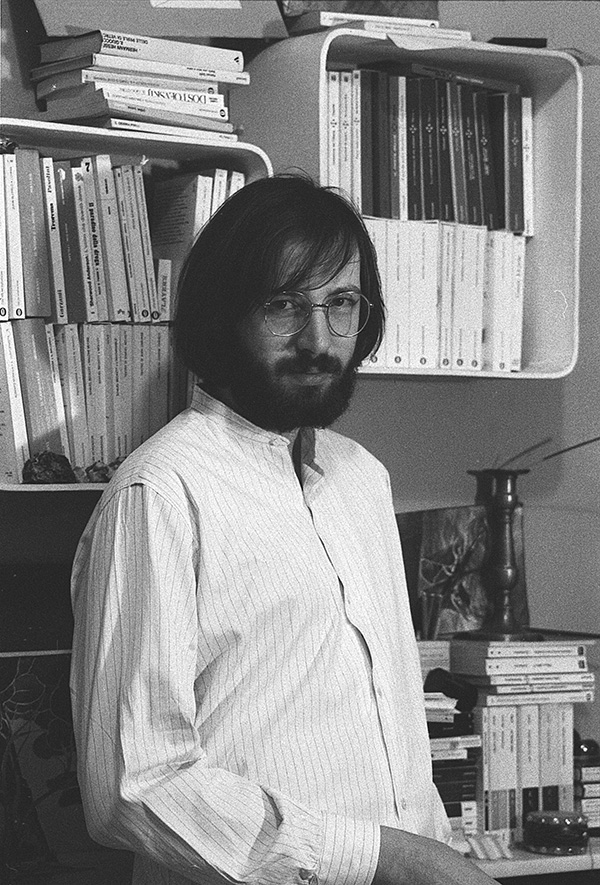

Tondelli enrolled at Dams in Bologna (‘He would have felt in touch with all his peers, he would have sought them out by enrolling at the University of Bologna, he would have found them only to realise that his own life would be played out in solitude and he would only have been able to unite with others through the solitary and distanced exercise of a practice as old as the world: writing. He would realise that he would never be a protagonist, but an observer’), attended film clubs, worked briefly in a theatre cooperative and for the cultural programmes of a free radio station.

In 1976 he joined the Management Committee of the Asioli Theatre in Correggio. ‘I have always needed artistic expression. Maybe in the beginning, when I was thinking about it, it was not writing. I chose it because it was the most direct medium, perhaps the simplest, through which I could put myself there, at night, and imagine a story without needing anything.

After all, I was very interested in cinema and entertainment, so much so that I enrolled in the DAMS in Bologna, with this very address. I would have liked to collaborate in this field. Mind you, writing has not been a fallback: it has always been the background to the search for an artistic activity through which I could live a little better’.

In Bologna, he attended Umberto Eco’s courses (a paper on wine culture almost led to an argument with the professor. This is how Eco recounts it: ‘Tondelli’s paper was exactly as he tells it: you can tell immediately from his summary that it was scintillating, full of unexpected quotations, certainly very personal. It was a fine non-fiction piece – and as far as I remember very well written: and this motivated the course of the argument, because I realised I was dealing with a young man of genius’) and Gianni Celati.

He wrote a first novel that he took to Aldo Tagliaferri, to the Feltrinelli publishing house and from whose rewriting the short stories of his debut book were born. ‘I have always written, since I was sixteen… For me, writing has always been linked to dreams, to desire. That first text – the typescript that preceded Altri libertini (Other Libertines) – many pages, a refined language, with also notable structural pretensions, sent to the Feltrinelli publishing house, reviewed in hindsight, becomes a very personal matter, not publishable, perhaps for this very reason. It is an inventory of the desires of a person of eighteen to nineteen years of age, with everything that can be found in a provincial life. Everything, in that kind of life, was very controlled, socially, on a family level’.

His frequentations in Bologna and, later, Milan also changed his perspectives and cultural references: Tondelli revised his mysticism and his yearning for the absolute, ‘turning – as he says himself – to the contemplation of the religions and philosophies of the Far East’; he read Lotta Continua daily, Re Nudo monthly and occasionally Lambda and ‘novelettes’, diaries. confessions, published in large numbers by small publishing houses, in this period, to ‘testify to a collective desire to take the floor’.

1979-1980

He wrote the short stories in his debut book, Altri libertini (Other Libertines), ‘so that each of them, while constituting a unit in itself, would merge into a substantially unitary novel which,’ says the author, ‘is that of my land and our generational myths’. Aldo Tagliaferri played an essential role alongside Tondelli: ‘The first thing I learnt in my apprenticeship under Aldo Tagliaferri, editorial editor and literary critic, was to rewrite. When I showed up in his office with a nice big book, the result of a year’s work, I expected immediate publication. I swear it did not even cross my mind that those four hundred pages would be reduced, scrambled, and finally forgotten to make room for what would become my debut book’.

He often moved from Correggio to Milan, ‘the city of fantasy, of freedom, of desire’, living in the sign of contemporaneity, losing himself in the ‘poetry of urban ghettos and suburbs’ and living ‘every hour its own dream’.

Altri libertini was published by Feltrinelli in January 1980 and immediately received great attention from the public, especially the young, and from critics.

It was seized by the judicial authorities for the crime of obscenity twenty days after its appearance in bookshops, when a third edition had already been prepared. The trial was held in Mondovì (Cuneo) in 1981 and acquitted the defendant and the publisher with a full verdict.

He graduated with a thesis on Epistolary literature as a problem of novel theory.

In February, he began collaborating with the daily newspaper ‘Il Resto del Carlino’ with Warriors in Correggio, an article on an ‘improvised and self-financed’ carnival on a Saturday afternoon by about fifteen boys.

In April, he left for military service, which saw him in barracks first in Orvieto and then in Rome.

1981

In February, in ‘Il Resto del Carlino’ and ‘La Nazione’, he began to publish a series of articles, ‘Il diario del soldato Acci’ (The diary of soldier Acci), in which he recounted episodes and atmospheres of the military service he was doing. These are ten ‘chronicles’, written ‘amidst impediments and constraints of all kinds’, which anticipate the themes of the novel that Pao Pao will soon begin to write. Tondelli is also thinking of a television adaptation: ‘a series of short-lived TV series starring Acci, his friends, and the army of Italy. The scansion in the short time of the story allows for an effective and almost natural television translation’.

1982

With the chronicles of a trip to ‘postmodern London that our immense and brisk youthful province continues to dream of’, the London calling ‘crossroads and short-circuit’ of behaviour, ills and musical fashions, published in March, his collaboration with the ‘Resto del Carlino’ came to an end.

A few months later, he began collaborating with ‘Linus’. The first article is Trip savanico on the new fashions of ‘postmodern’ Bologna, between galleries and discotheques, with all the young people of ‘creative Bologna dancing to the tribal interferences of electronic music’, a look at the ‘twenty-year-old fauna, extrovert and creative, who practice the contiguous territories of theatre, figurative art, performance, music’. Tondelli also moved to Bologna and his acquaintances include Andrea Pazienza and Francesca Alinovi.

June saw the publication by Feltrinelli of his second novel, Pao Pao, which plays on the acronym PAO, which stands for Picchetto Armato Ordinario (Ordinary Armed Pole) and already indicates the content: the description of that ‘rite of passage’ that is the barracks.

1983

Starts thinking about a novel about the early 1980s, which should have been entitled A Postmodern Weekend. He wrote the first three chapters and then the project was abandoned.

‘It was an attempt for me, which then remained on paper, to make a novel of my own by translating, transcribing the talk of the parties of those years. Basically there had to be five, six, seven parties, one in Florence, one in Bologna, one in Milan, one in London, in which they were described with a very sung, almost poematic, very mixed language, with the dialogues inserted, without inverted commas in the text, with a rather strange language… Even as readability it was very strong, too much perhaps…’

There are also other reasons to explain the abandonment of the project: the discovery of the excesses linked to those ‘euphorias’, the murder of Francesca Alinovi…: ‘For me, the 1980s already ended there, in 1983, during that weekend where, under the appearance of a mobile fiesta of happy, and even wild, young people, the madness of relationships, the excess of certain rituals and even fear were revealed. After that it was just a time of observation and reflection, of working on the more or less autobiographical material’.

He began to plan the novel Rimini, the elaboration of which would take him until 1985.

1984

In the early months of the year, he wrote the first draft of the play Dinner Party, in his house in Via Fondazza in Bologna. ‘It is a story of thirty-year-olds, of a generation to which it is difficult to attach labels, a somewhat violent and somewhat sophisticated drama. I finished it a week ago (ed. 12 April). I have another month to work on it, but I am satisfied. Comedy was an unexplored genre for me, and it excites me. I plan to stage it in Florence next season… I was stuck on a new novel (ed. Rimini) I could not go on, could not find the right ending. Strangely enough, liberation came with theatre in mind. Dinner party I wrote it on the spur of the moment. Two weeks of work day and night. The plot was that of an old story of mine, which was supposed to become a novel and instead turned into an original, tight comedy’.

He is often in Florence, where the youth scene, including exhibitions, avant-garde theatre, fashion shows and parties is exuberant: ‘I felt I was in the right place at the right time. A bit like when I attended DAMS, in Bologna, in the hot years between 1975 and 1979… This is how my years in Florence passed. In so many houses, in so many flats, in so many parties until the morning that gave me the sensation – tangible and concrete – of living in a city where I did not have much time left to reflect on my intimate troubles; or, if this happened, where I felt the protection, the understanding, the embrace of the city itself that magically accorded with those reflections’.

In Florence at the Teatro di Rifredi, presented by Anna Maria Papi and with a set design composed of works by Monica Sarsini, he held a lecture whose central body was the reading of very short quotations in the form of fragments on the theme of abandonment (‘abandonment of love, abandonment of the beloved, abandonment of things or perhaps even of reality’).

The first draft of Notes to Friends begins: ‘This is the last note I write. The first one dates back to April eighty-four, one night in Florence. Since then many things have changed in my life and perhaps the most important concerns these pages that are no longer called ‘Notes for a Phenomenology of Abandonment’, but simply Notes to Friends’.

He meets Francois Wahl of Editions Seuil in Paris, the publisher who will publish the French edition of Pao Pao. A relationship of mutual esteem began. Over the years, Wahl became a very important interlocutor, to whom Tondelli subjected all subsequent literary projects to critical scrutiny: ‘For some writers, Calvino was important, for others, Celati’s lesson. In my case, I must mention the names of Aldo Tagliaferri and Francois Wahl in France. It is not, however, that I have had other interlocutors. I would have liked to have had them, because this helps me discover what I do not know’.

1985

In May, the novel Rimini was published, marking Pier Vittorio Tondelli’s move from the Feltrinelli publishing house to Bompiani.

The book was greeted by critics as a consumer novel, a label that did not appeal to the writer, who saw Rimini as an attempt to describe the Adriatic Riviera ‘as a “container” of different stories… a fresco, perhaps a symphony, of the Italian reality of these years, and of the various ways – sentimental, dramatic, existential – of telling the story’.

It is one of the best-selling books of the summer and becomes, above all, a lifestyle phenomenon. It was presented, together with Lu Colombo’s record hit of the same name, with a buffet in the garden and dancing in Fellini’s salons, at the Grand Hotel, by Roberto D’Agostino, on a July evening ‘under the banner of the collective imagination about Rimini’, in conjunction with the inauguration of the Bolognese exhibition (same party organisation) Anniottanta.

There is also a controversy: the cancellation of the presentation of the novel in Baudo’s lounge on Domenica in, already announced by ‘Sorrisi e Canzoni TV’. The ‘cancellation’ has the flavour of a real ‘political’ censorship, while the official motivation states: ‘Just as films and videos forbidden to minors are not accepted, so it is for literary works that narrate, among other things, episodes of sex’. There was also disappointment on the part of those who had collaborated on the non-canonical presentation of the book: the fashion designer Enrico Coveri, who had prepared a fashion show in bathing costumes, and a group of Rimini photographers who had edited a videotape to be aired with the interview with Tondelli, at the express request of the programme.

Through the columns of ‘Linus’ with an article entitled Gli scarti, on the new realities of youth, the ‘Under 25 Project’ actually got underway, which a few months later took advantage of the collaboration with the small publishing house Il Lavoro Editoriale of Ancona. Tondelli writes: ‘The Under 25 project is launched, and our wish is that, year by year, as the age of the participants increases, it will become a fun and enjoyable appointment with the new generations’ ways of telling stories, a sort of game in which, as readers, we will not tire of participating’. By 31 December, the deadline for participating in the first volume, four hundred texts had reached the editorial office of Lavoro Editoriale, and already in early 1986, another hundred.

He began to collaborate with ‘L’Espresso’ and the ‘Corriere della Sera’, but the relationship with the Milanese newspaper was interrupted after an interview with the Magazzini (Dialogues in the Street with the Magazzini No Longer Criminal) published in December.

For his new version of the comedy in two acts, entitled La notte della vittoria (Dinner Party), submitted to the 38th edition of the Riccione-Ater Theatre Prize, he was awarded the Special Prize in memory of Paolo Bignami, with the following motivation: ‘A work that, in the apparently traditional setting of a bourgeois environment, expresses, with dry and ironic dialogue, the moods and anxieties of a generation of the 1980s and marks the entry of an emerging storyteller into the theatre’.

He also began working on a number of film projects related to his literary works. ‘My interest in a cinema that is above all cinema made up of dramatic stories and not just boorish slang comedies will be realised in a film based on my previous book Altri libertini (Other Libertines), which Daniele Segre is trying to ‘edit’ with other young directors from the Milan area such as Giancarlo Soldi. It will be an episodic film, each episode a young director and a different cinematographic style: it will be a film that does not conceal the ambition of proposing itself as the eventual leader of a new Italian cinematography’. The film will never be made, like Rimini, about which Tondelli began to write an initial draft of the screenplay with Luciano Mannuzzi, the director. ‘Basically, I imagined that an end-of-the-world atmosphere was gripping the summer holiday Babylon so that stories and plots could be told that, precisely because they were placed in such a container, would become stronger. More representative. And so the tale of meaninglessness, futility, frivolity, stupidity, but also of emotion, of exciting moments of life, of seaside sex encounters, all seemed much stronger to us when seen under this sort of bell jar of a real nuclear danger that no one seemed or wanted to notice. This project, also due to internal inconsistencies, was abandoned and replaced, although it remains as a general atmosphere whose elaboration is announced to be imminent’.

On 30 November, Gianfranco Zanetti’s play, based on two short stories by Altri libertini, ‘Postoristoro’ and ‘Autobahn’, makes its national debut at the Asioli Theatre in Correggio.

In December, he began his collaboration with the monthly magazine ‘Rockstar’, which lasted until 1989. He signed a successful ‘Culture Club’ column (Boy George’s group certainly played a role in the choice of the name), which between reading tips, music reports and emotions became a sort of ‘diary in public’ and a very direct conversation with the monthly magazine’s young readers.

1986

He moved to Milan, to a flat in Via Abbadesse, number 52: ‘I bought a Tibetan Tanka, my first Tanka. It is an 18th century piece. It represents the Paradise of Amithaba, the Buddha of infinite light. I will have to restore it a bit, but I hope it will protect my new home’.

Trips to Europe are frequent, including Paris, Berlin, a city he also visited in previous years, and Amsterdam.

The theme of travel also became the ‘background’ for a number of short stories (Ragazzi a Natale, Questa specie di patto) published in ‘Per lui’ and in ‘Nuovi Argomenti’ (Pier in January).

He edited the first volume of the ‘Under 25 Project’, Giovani Blues, which came out in May 1986 and featured short stories by Andrea Canobbio, Andrea Lassandari, Roberto Pezzuto, Giuliana Caso, Paola Sansone, Rory Cappelli, Alessandra Buschi, Giancarlo Visconvich, Claudio Camarca, Vittorio Cozzolino and Gabriele Romagnoli. The underlying theme is identified in ‘a youthful condition contended between everyday life and adventure, a light or at best bittersweet condition, never desperate or tragic….’.

For Baskerville Editions, a small publishing house in Bologna, which made its debut with this very text, it published Biglietti agli amici , a ‘personal’ book, for the few, ‘a handcrafted, carefully edited, precious book’. Initially ‘it was supposed to be a “livre d’art”: fifty copies in all and the astrological and angelic tables drawn by an artist’. In the edition that goes to press, however, the book has a particular structure linked to the hours of the day marked by the angelic and astrological tables drawn by Barrett. Only a few copies of the book are printed, a hundred or so. One version, the one intended for the people to whom the ‘cards’ are dedicated, bears the full name, almost as a personalisation of the book. This edition has a private character and is not offered for sale. The edition that arrives in bookshops, with all copies autographed by the author, on the other hand, although identical to the private edition, substitutes, in the dedications, the initials of the friends’ names for the full names. To maintain the private nature of the publication, the writer initially asked the journalists to whom he had sent it not to talk about it.

1987

In March, he took part in the conference ‘Il racconto: attualità della letteratura’ in Trento, with an important paper entitled Un momento della scrittura.

He edited the second volume of the ‘Under 25 Project’, Belli & perversi, which was published in December 1987 and presented short stories by Andrea Mancinelli, Francesco Silbano, Romolo Bugaro Giuseppe Borgia, Renato Menegat, Andrea Demarchi and Tonino Sennis. There is no precise theme, but certainly more attention ‘to the literary aspects of the proposal’. He is working on the project for an ‘editorial series’, Mouse to Mouse, for the publisher Mondadori, which ‘wants to explore those cultural territories that are not immediately ascribable to literature and its practices, places that are not marginal, not emerging in society. It therefore looks for narratives in the world of fashion, advertising, figurative arts, performing arts, rock…’

1988

In spring, with a cover design by Luis Frangella, the first two ‘Mouse to Mouse’ titles, chosen by Tondelli, are published: Fotomodella by Elisabetta Valentini and Hotel Oasis by Gianni De Martino.

At Columbia University with Alain Elkann, Enzo Siciliano, Manfredi Piccolomini, David Leavitt presents the American issue of the magazine ‘Nuovi Argomenti’, which contains his short story Pier’s January.

Holds a series of conferences in various Italian cities on the Under 25 project.

Starts work on the novel Separate Rooms.

1989

In March, he held a series of meetings with high school students in Guastalla, intended as ‘a seminar on writers, the Po and Emilia, to invite them to read and discover the writers of their land, compare places and descriptions’.

In spring, he published his novel Camere separate (Separate Rooms) with Bompiani, which represents a sort of turning point. It is ‘the story of a journey marked out in three concentric and contiguous movements-chapters like an operetta of ambient music. The themes of death, mourning for the loss of a companion, religiosity, the mother, the country, travels, and friendship constitute the narrative fabric of a complex search for interiority and insight’.

He collaborated with Luciano Mannuzzi, writing various versions of the subject that would later form the basis of the film, Sabato Italiano, released in cinemas in 1992.

With Alain Elkann and Elisabetta Rasy, he worked on the project for a literary magazine, with a monographic theme, ‘Panta’, whose first issue came out in January 1990, published by Bompiani.

For the magazine, she plans a trip to Grasse, on the Côte d’Azur, on the trail of the writer Frederick Prokosch, whom she would have liked to interview. Suddenly, however, news arrived of the writer’s death. He made the trip himself and also took a series of evocative photographs, which he took to accompany the text.

He meets critic Fulvio Panzeri for a long conversation to be published in a volume on ‘new Italian fiction’, announced by Transeuropa-Il lavoro editoriale in Ancona.

He met Giorgio Bertelli, of Brescia’s L’obliquo editions, for the project of a new book in a limited edition and three hypotheses to be evaluated: an essay on Arbasino, the reprise of the short story Pier in January, a book version of Viaggio a Grasse, text and photographs.

1990

He published a long story on ‘his’ soundtracks, Quarantacinque giri per dieci anni, in Canzoni, an anthological volume (containing stories by Palandri, Manfredi, Lodoli , Van Straten) for Leonardo editore.

He took an active part in organising the exhibition Ricordando fascinosa Riccione, organised for the 40th Riccione-Ater Prize for Theatre and carried out accurate archive and bibliographic research on the relationship between twentieth-century writers and the Adriatic Riviera. He also wrote an extensive essay for the catalogue, ‘Cabine! Cabine!’, in which he re-evaluates writers such as Guareschi, Scerbanenco, and Arfelli and edits an anthology on the literary images of Riccione and the Adriatic Riviera.

Together with Fulvio Panzeri, he began working on the project Un weekend postmoderno (A Postmodern Weekend), which began as a hypothesis to bring together in a broad and complex ‘critical novel’ all the journalistic, literary and non-fiction production elaborated by the writer during the 1980s. After a classificatory and critical examination of the available material, the project was hypothesised in two volumes, one dedicated to the ‘chronicles of the 1980s’ and the other, to the ‘writings of the 1980s’. During the summer, the first volume is organised, published in the autumn by Bompiani.

Tondelli also edits the third volume of the ‘Under 25 Project’, Papergang, which is published in November by Transeuropa and features the stories of Silvia Ballestra, Guido Conti, Raffaella Venarucci, Giuseppe Culicchia, Alessandro Comoglio and Frediano Tavano, Ageliki Riganatou, and Andrea Zanardo, which give rise to ‘a volume different from the previous ones, certainly more reflective….’.

The French edition of the novel Rimini was published by Seuil, on which Tondelli worked, with translator Nicole Sels, on a substantial revision of the text.

1991

In April he moved from Milan to Bologna.

After a trip to Tunisia, he was hospitalised in Reggio Emilia at the end of the summer. He chooses silence with respect to his illness (AIDS). He only meets a few friends and in his hospital bed he only writes brief notes on a literary project that is close to his heart and that he will not succeed in realising, Sante messe: ‘Structure of the “Masses”…. 1) Twelve like the signs of the zodiac and their respective patron angels. 2) Twenty-three like the letters of the angelic alphabet ‘writing of the angels’. Perhaps ten texts’.

He also revises a number of already published books, to arrive at a final version. For Altri libertini he prepares a partial revision of the text aimed at highlighting errors and modifying linguistic situations (especially profanity) within the stories. For Tickets to Friends he hypothesises new addressees and new tickets. Also in this case the work is not completed.

He returns to the Catholic religion.

He dies on 16 December 1991. He is buried in the small cemetery of Canolo, a small hamlet of Correggio.

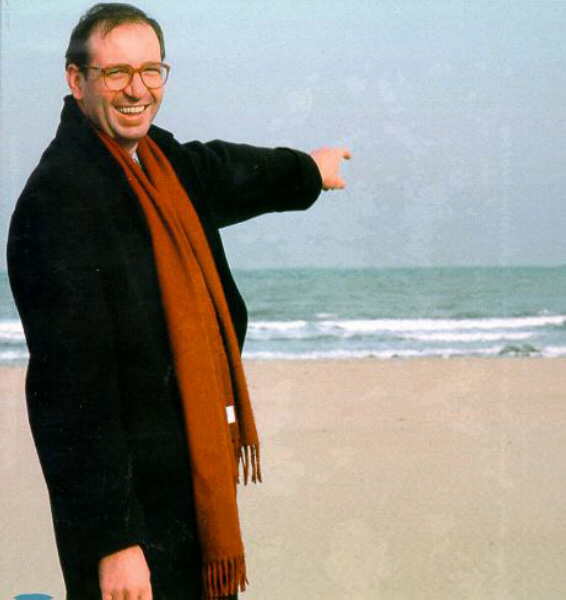

Pier Vittorio Tondelli

Pier Vittorio Tondelli